-

“. . . [H]istory, captured in tangible form, from an era long gone yet still very much vivid in the memory and pride of the people who so dearly cherished them.” - Statement of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Fatou Bensouda, at the opening of Trial in the case against Mr. Ahmad Al-Faqi Al Mahdi[i]

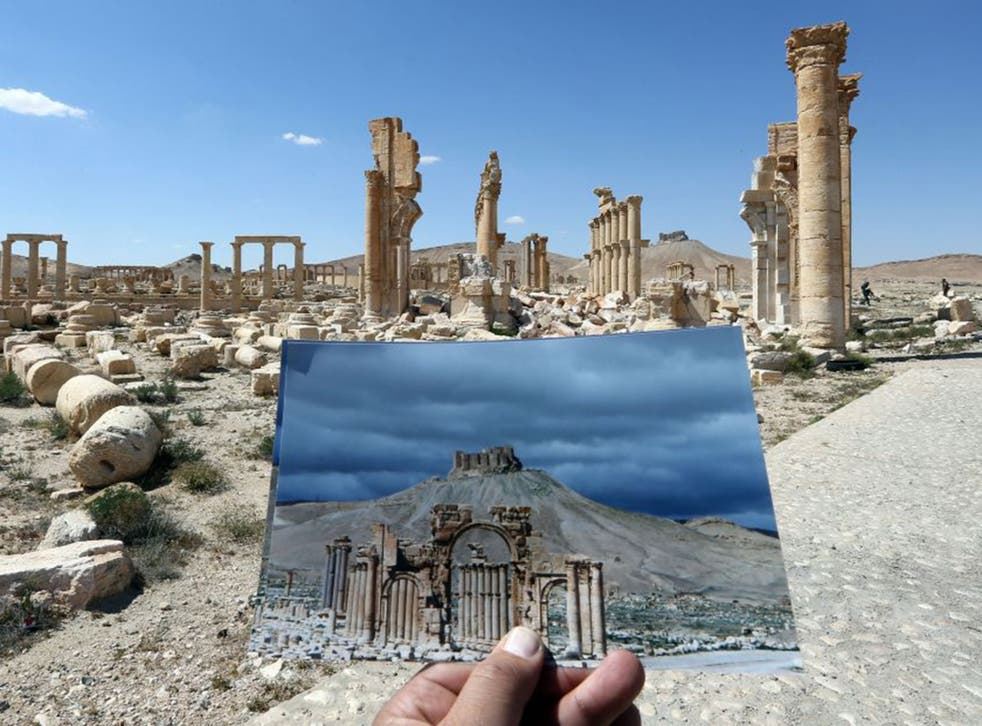

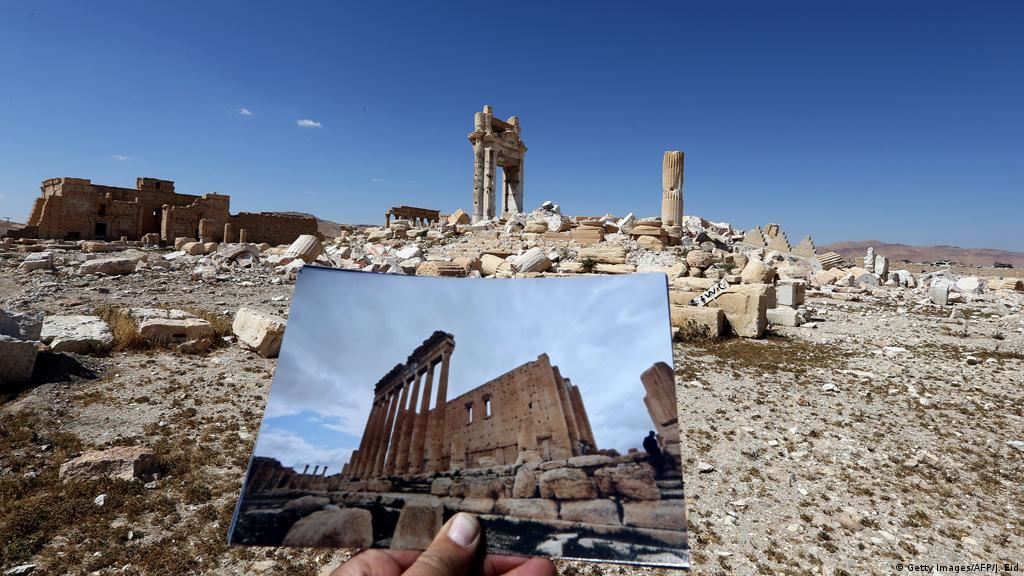

Cultural property and heritage have enabled an important paradox: history to be present. They are our remaining and, hence, tenuous links to past events. Yet despite their precious value, these remnants have, very literally, been under severe- and even very recent- attack. A significant travesty occurred when ISIS captured the ancient city of Palmyra twice in 2015 and 2016, the group committed several acts of cultural violence, irreparably destroying ancient sites and treasures dating as far back as to the Roman Empire and violently decapitating an archaeologist for his silence on the location of an artifact.[ii] Irina Bokova, the Director-General of UNESCO at the time, condemned ISIS’s attack: “The systematic destruction of cultural symbols embodying Syrian cultural diversity reveals the true intent of such attacks, which is to deprive the Syrian people of its knowledge, its identity and history . . .”, and called the actions a “war crime”.[iii]

Even now, another military campaign has been endangering the safety and existence of a culture's heritage. Since February 2022, the Russian Federation's ("Russia") war against Ukraine has destroyed many objects and sites. UNESCO has verified already that the invasion has damaged over 100 of Ukraine's cultural sites, including religious buildings, monuments, and museums.[iv] Among the destroyed sites is the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, which as a result, also led to the losses of 25 artworks of Maria Prymachenko.[v] As Russia's invasion continues, there has been an urgent race (as media reports have aptly called) for the survival of Ukrainian cultural heritage.[vi] Within Ukraine, measures among institutions and art professionals have included boxing up cultural objects in museums for safekeeping and razor wiring museum exterior against attacks.[vii] UNESCO has been working with institutions and individuals to help protect Ukraine's heritage and monitor ongoing damages.[viii] In light of this conflict, Audrey Azouley, the current UNESCO Director-General, has emphasized that "the international community has a duty to protect and preserve" cultural heritage in Ukraine as both "a testimony of the past . . . [and] a catalyst for peace and cohesion in the future."[ix]

In light of such ongoing dangers of armed conflict, international law has established sources and mechanisms specifically for the purpose of protecting cultural heritage. In 2016 the International Criminal Court (ICC) for the first time ruled that attacks against cultural property constitute a war crime in Prosecutor v. Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi (See also World Heritage).[x] In 2012 armed groups of Ansar Dine and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) seized Timbuktu as part of an internal conflict in Mali.[xi] During this time, ten of “the most important and well-known” Timbuktu sites were attacked and destroyed.[xii] The ICC sentenced Al Mahdi, who was responsible for the attacks, to nine years of imprisonment.[xiii]A Reparations Order of 2.7 million euros in expenses for individual and collective reparations to the Timbuktu community followed this verdict.[xiv] To comprehend how cultural property protection in armed conflict works in international law, it is important to understand the two important and relevant sources of law: treaty law and customary international law.Treaty law refers to texts like treaties and conventions to which signing state parties are legally bound.[xv] The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (“1954 Hague Convention”) is the first – and the most important – international treaty for cultural property protection in armed conflict situations, and 133 nations have become State Parties.[xvi] The 1954 Hague Convention applies to the State Parties “in the event of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of [them], even if the state of war is not recognized by, one or more of them” (Article 18(1)). But as a treaty law, the Convention is not binding on states that have not signed it.[xvii] Two Protocols to the Convention followed in 1954 and 1999 respectively. It is relevant to note that both Russia and Ukraine are State Parties to the 1954 Hague Convention.

Customary international law refers to rules that have gained status as laws through their ‘customary’ practice and application in the international community. [xviii] Conventions or specific provisions can gain customary law status. For

- instance, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the two Additional Protocols (“Additional Protocol I” and “Additional Protocol II”) have formed a significant basis of customary international humanitarian law (IHL) today.[xix] While Additional Protocol I

- covers situations of international armed conflict, Additional Protocol II covers situations of non-international armed conflict. The International

- Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) conducted a study on customary IHL and listed 161 rules, which the Cambridge University Press published in two volumes.[xx] According to this study, “[t]he fundamental principles of protecting and preserving cultural property in the [1954 Hague Convention] are

and weaknesses that scholarship and recent cases have illustrated. Some of the most discussed topics have been:

- The absence of a central enforcement entity in the 1954 Hague Convention, relying on each State’s individual and domestic mechanisms.[xxxi] Neither the Convention nor the Protocols specify appropriate punishment or prosecutorial mechanisms for those who violate the provisions.[xxxii]

- As mentioned previously, treaties and conventions are only binding to the parties that entered into them. As of 2021, while 133 State Parties have ratified the 1954 Hague Convention, only 110 have ratified the first Protocol and 84 have ratified the second Protocol.[xxxiii] This means that provisions in the second Protocol may not even apply to all State Parties for the 1954 Hague Convention.[xxxiv]

- Uncertainty as to whether the 1954 Hague Convention applies to armed non-state actors in non-international conflicts like rebels or al-Qaeda militants in Mali and Syria recently.[xxxv] According to Article 19 of the Convention: “each party to the conflict shall be bound to apply, as, a minimum, the provisions of the present Convention which relate to respect for cultural property.

- Some scholars have interpreted this provision as applicable to non-state actors because of the word “party” in lieu of capitalized “State Party” or “High Contracting Party.”[xxxvi] On the other hand, the 1999 second Protocol’s expanded coverage of cultural property protections in non-international armed conflicts only uses “Parties” in its capitalized form (Article 22(1)), which has also led to an interpretation that the Protocol excludes third parties or non-state actors in non-international conflicts.[xxxvii]

- Harmful Impact of “parties”/“Parties” dichotomy: While Article 19(3) of the Convention allows UNESCO to offer services to the “parties” to non-international armed conflict, Article 23 then states that only “High Contracting Parties” may “call upon [UNESCO] for technical assistance in organizing the protection of their cultural property, or in connexion with any other problem arising out of the application of the present Convention or the Regulations for its execution”. This textual dichotomy has arguably given way to a structural “asymmetry” between State Parties and non-state actors in the Convention and its Protocols, which further created real problems for cultural property protection in recent years.[xxxviii]A case in point is the efforts of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in Mali when it tried to communicate with UNESCO and return ancient manuscripts it had seized during conflict with Islamist groups.[xxxix] In the end, the manuscripts were seized and destroyed. This event demonstrated how the asymmetry for armed non-state actors in the Convention created a “unidirectional” communication mode between UNESCO and the actors, which led to damages to cultural property.[xl]

-

Updates/Developments

- In 2020, the ICRC and the Blue Shield entered into a Memorandum of Understanding to work together in protecting cultural property during armed conflict situations.[xli]

- In June 2021, the Office of the Prosecutor issued a new Policy on Cultural Heritage to raise awareness and strengthen the protection for cultural property.[xlii]

-

Controlling Law

- Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, Article 56 (1907)

- Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention (1954)

- Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed conflict (1954)

- Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (1999)

- Geneva Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (1949)

- Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) (1977)

- Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II) (1977)

- Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970)

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1972)

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Articles 8(b)(ix) & (e)(iv) (1998)

- Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15 (2016)

-

Overseeing Organizations

- UNESCO

- International Criminal Court (ICC)

- United Nations

- ICRC

- International alliance for the protection of heritage in conflict areas (ALIPH)

- Committee for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

widely regarded as reflecting customary international law, as stated by the UNESCO General Conference and by States which are not party to the Convention.”[xxi]

Cultural Property

Under the 1954 Hague Convention, “cultural property” is defined under Article 1 as:

(a) movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people, such as monuments of architecture, art or history, whether religious or secular; archaeological sites; groups of buildings which, as a whole, are of historical or artistic interest; works of art; manuscripts, books and other objects of artistic, historical or archaeological interest; as well as scientific collections and important collections of books or archives or of reproductions of the property defined above;

(b) buildings whose main and effective purpose is to preserve or exhibit the movable cultural property defined in sub-paragraph (a) such as museums, large libraries and depositories of archives, and refuges intended to shelter, in the event of armed conflict, the movable cultural property defined in sub-paragraph (a);

(c) centers containing a large amount of cultural property as defined in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b), to be known as `centers containing monuments’

The Additional Protocols to the 1949 Geneva Conventions also contain provisions specifically for protection of “cultural objects and places of worship” – “[w]ithout prejudice to the provisions of the [1954 Hague Convention]” (Article 53 of Additional Protocol I; Article 16 of Additional Protocol II). In both texts, the provisions refer to “historic monuments, works of art or places of worship which constitute the cultural or spiritual heritage of peoples.” A noteworthy distinction between texts lies in their respective descriptions of the heritage: “of every people” or “of peoples”. According to Rule 38 of ICRC’s Customary IHL, the Additional Protocols intended to protect “only a limited amount of very important cultural property” that belongs to the heritage of “mankind” as a whole.[xxii]

Protection of Cultural Property

The 1954 Hague Convention describes protection in terms of “safeguarding” of and “respect” of cultural property (Article 2). “Safeguarding” entails taking measures for their cultural property during peacetime against foreseeable effects of an armed conflict (Article 3). The second Protocol of 1999 clarifies that such measures “include, as appropriate, the preparation of inventories, the planning of emergency measures for protection against fire or structural collapse, the preparation for the removal of movable cultural property or the provision for adequate in situ protection of such property, and the designation of competent authorities responsible for the safeguarding of cultural property” (Article 5).

“Respect” covers actions such as “refraining from any use of the property [within their territory and other Parties’ territories] and its immediate surroundings or of the appliances in use for its protection for purposes which are likely to expose it to destruction or damage in the event of armed conflict; and . . . from any act of hostility, directed against such property” (Article 4(1)). “Respect” further requires a Party “to prohibit, prevent and, if necessary, put a stop to any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property” and to “refrain from requisitioning movable cultural property situated in the territory of another High Contracting Party” (Article 4(3)).

However, under Article 4(2), the 1954 Hague Convention excuses a Party from obligations to respect cultural property “in cases where military necessity imperatively requires such a waiver”. The second Protocol of 1999 clarified that this waiver may only apply for an “act of hostility” against cultural property when the object has “by its function, been made into a military objective” and “there is no feasible alternative available to obtain a similar military advantage to that offered by directing an act of hostility against that objective” (Article 6(a)). Moreover, the second Protocol states that only an “officer commanding a force the equivalent of a battalion in size or larger, or a force smaller in size where circumstances do not permit otherwise” may decide on whether to invoke the waiver (Article 6(c)). By narrowing the applicability of the “military necessity” waiver, the Second Protocol strengthened the Hague Convention’s protection for cultural property.[xxiii]

Special vs. Enhanced Protection

The 1954 Hague Convention further provides special protection to “a limited number of refuges intended to shelter movable cultural property in the event of armed conflict, of centers containing monuments and other immovable cultural property of very great importance” (Article 8(1)). To qualify for special protection, the cultural property must:

(a) . . .[be] situated at an adequate distance from any large industrial center or from any important military objective constituting a vulnerable point, such as, for example, an aerodrome, broadcasting station, establishment engaged upon work of national defense, a port or railway station of relative importance or a main line of communication;

(b). . . not [be] used for military purposes.

But should the property’s location not satisfy the first condition of “adequate distance” from an important military objective, it may still receive special protection “if the High Contracting Party asking for that protection undertakes, in the event of armed conflict, to make no use of the objective and particularly, in the case of a port, railway station or aerodrome, to divert all traffic there from [during peacetime]” (Article 8(5)).

A cultural property gains special protection upon its listing on the International Register of Cultural Property under Special Protection (Article 8(6)). Under Article 9, the Parties are required to “ensure the immunity of cultural property under special protection by refraining, from the time of entry in the International Register, from any act of hostility directed against such property and, except for the cases provided for in paragraph 5 of Article 8, from any use of such property or its surroundings for military purposes.”[xxiv] However, the conditions for special protection limit the number of eligible cultural property.[xxv] For instance, one of the challenges has been the difficulty of fulfilling the condition of the “onerous distancing requirements” because the only eligible cultural objects would be those “located in a mountain wilderness or remote swamp” – while “many of the objects envisioned for protection are located in cities and are surrounded by military objectives.”[xxvi]

The second Protocol replaced the “special protection” with “enhanced protection”, expanding the applicability of this protection system to more cultural property.[xxvii] For “enhanced protection,” under Article 10 of the Protocol, a cultural property must satisfy three conditions:

1) cultural heritage of the greatest importance for humanity;

2) protected by adequate domestic legal and administrative measures recognizing its exceptional cultural and historic value and ensuring the highest level of protection;

3) not used for military purposes or to shield military sites with a declaration from the Party with control over the cultural property that confirms the property will not be so used.

The Protocol stipulates that while the “enhanced protection” provisions are without prejudice to the 1954 Hague Convention’s “special protection” provisions, if “cultural property has been granted both special protection and enhanced protection, only the provisions of enhanced protection shall apply” (Article 4(b)).

Prosecution and Sanctions

Under Article 28 of the 1954 Hague Convention, State Parties must implement “within the framework of their ordinary criminal jurisdiction, all necessary steps to prosecute and impose penal or disciplinary sanctions upon those persons, of whatever nationality, who commit or order to be committed a breach of the . . . Convention.” The second Protocol enumerates five “Serious Violations” that each State Party should adopt as criminal offences under its domestic law and make punishable by appropriate penalties (Article 15). These actions are:

a) making cultural property under enhanced protection the object of attack;

b) using cultural property under enhanced protection or its immediate surroundings in support of military action;

c) extensive destruction or appropriation of cultural property protected under the Convention and this Protocol;

d) making cultural property protected under the Convention and this Protocol the object of attack;

e) theft, pillage or misappropriation of, or acts of vandalism directed against cultural property protected under the Convention.

Article 16 of the Protocol further provides that a Party shall “take the necessary legislative measures to establish its jurisdiction over the [above] offences” for three cases:

1) when such an offence is committed in the territory of that State;

2) when the alleged offender is a national of that State;

3) in the case of offences set forth in sub-paragraphs (a) to (c) of the first paragraph of Article 15, when the alleged offender is present in its territory.

In addition, the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court recognizes the last two offences (Article 15(1)(d) and (e) of the 1999 second Protocol) as war crimes for both international and non-international armed conflict situations:[xxviii] “[i]intentionally directing attacks against buildings dedicated to religion, education, art, science or charitable purposes, historic monuments . . . provided they are not military objectives” (Article 8(2)(b)(ix) and Article 8(2)(e)(iv)).[xxix] The Al Mahdi case (discussed above) was the first case in which the ICC applied Article 8(2)(e)(iv)[xxx] and convicted a party as guilty for the war crime of intentionally directing attacks against dedicated to religion and historic monuments.

Problems/Issues

Despite the existence of treaty and customary law for cultural property protection in armed conflicts, there are still issues

Further Reading

- Gary Solis, Attacks on Cultural Property, in The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War 562 (3d ed. 2021)

- Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, The Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Goods: A Long and Ignoble History Ancient Rome Live (Last updated Nov. 9, 2021), https://ancientromelive.org/the-illicit-trafficking-of-cultural-goods-a-long-and-ignoble-history/

- Intersections in International Cultural Heritage Law (Anne-Marie Carstens & Elizabeth Varner eds. 2020)

- Culture under Fire: Armed Non-State Actors and Cultural Heritage in Wartime, Geneva Call (2018), https://genevacall.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Cultural_Heritage_Study_Final.pdf

- Marina Lostal, International Cultural Heritage Law in Armed Conflict: Case-Studies of Syria, Libya, Mali, the Invasion of Iraq, and the Buddhas of Bamiyan (2017)

- Patty Gerstenblith, The Destruction of Cultural Heritage: A Crime Against Property or a Crime Against People?, 15 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L. 336, 352 (2016)

- Patty Gerstenblith, Beyond the 1954 Hague Convention, in Cultural Awareness in the Military: Developments and Implications for Future Humanitarian Cooperation 83, 93 (Robert Albro & Bill Ivey eds. 2014)

- Kevin Chamberlain, War and Cultural Heritage: A Commentary on the Hague Convention 1954 and its Two Protocols (2d ed. 2013)

- Zoe Howe, Can the 1954 Hague Convention Apply to Non-state Actors?: A Study of Iraq and Libya, 47 Tex. Int’l L.J. 403, 413 (2012)

- Patty Gerstenblith, Protecting Cultural Heritage in Armed Conflict: Looking Back, Looking Forward, 7 Cardozo Pub. L. Pol'y & Ethics J. 677 (2009)

- Roger O’Keefe, The Protection of Cultural Property in Armed Conflict (2006)

- David Keane, The Failure to Protect Cultural Property in Wartime, 14 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. (Special Section: Art & War) (2004)

Footnotes

[i] Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15, Statement of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Fatou Bensouda, at the opening of Trial in the case against Mr Ahmad Al-Faqi Al Mahdi (Aug. 22, 2016), https://www.icc-cpi.int/pages/item.aspx?name=otp-stat-al-mahdi-160822.

[ii] See Jasmine Ho, The Ancient City of Palmyra under the Syrian Civil War, ArcGIS StoryMaps

(May 7, 2021), https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/945b98034b694bca9d907140603489f7; Brigit Katz, Ancient City of Palmyra, Gravely Damaged by ISIS, May Reopen Next Year, Smithsonian Mag. (Aug. 29, 2018), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ancient-city-palmyra-gravely-damaged-isis-may-reopen-next-year-1-180970160/; Sarah Cascone, Nearly Destroyed by ISIS, the Ancient City of Palmyra Will Reopen in 2019 After Extensive Renovations, ArtNet (Aug. 27, 2018), https://news.artnet.com/art-world/syria-isis-palmyra-restoration-1338257.

[iii] Director-General of UNESCO Irina Bokova firmly condemns the destruction of Palmyra's ancient temple of Baalshamin, Syria, UNESCO (Aug. 24, 2015), http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1339/.

[iv] Damaged cultural sites in Ukraine verified by UNESCO, UNESCO (Apr. 19, 2022), https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco?hub=66116. See also Deepa Shivaram, UNESCO says 53 cultural sites in Ukraine have been damaged since the Russian invasion, NPR (Apr. 2, 2022), https://www.npr.org/2022/04/02/1090475172/unesco-ukraine-cultural-sites-damage; At least 53 culturally important sites damaged in Ukraine- Unesco, Guardian (Apr. 1, 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/01/at-least-53-culturally-important-sites-damaged-in-ukraine-unesco

[v]Safeguarding the Cultural and Historical Heritage of Ukraine: Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch Statement, Smithsonian (Mar. 3, 2022), https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/releases/safeguarding-cultural-and-historical-heritage-ukraine.

[vi]See e.g. Katie Razzall, Ukraine: The race to save the country's artistic treasures, BBC (Mar. 4, 2022), https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-60603406; Bernat Armangue, At Ukraine's largest art museum, a race to protect heritage, AP News (Mar. 5, 2022), https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-travel-europe-art-musuems-musuems-768ce266673b85965edc8367c2257370.

[vii]Racing to protect Ukraine's cultural heritage, U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Italy (Mar. 28, 2022), https://it.usembassy.gov/racing-to-protect-ukraines-cultural-heritage/; Armangue, At Ukraine's largest art museum, supra note vi.

[viii]Endangered heritage in Ukraine: UNESCO reinforces protective measures, UNESCO (last updated Mar. 24, 2022), https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/endangered-heritage-ukraine-unesco-reinforces-protective-measures.

[ix]War in Ukraine, UNESCO (last visited Apr. 20, 2022), https://www.unesco.org/en/ukraine-war.

[x]Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15, Judgment & Sentence, ¶¶ 52, 64 (Sept. 27, 2016), https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2016_07244.PDF. See also Paul Williams, Tear It All Down: The Significance Of The al-Mahdi Case And The War Crime Of Destruction Of Cultural Heritage, HuffPost (last updated Sept. 30, 2016), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/tear-it-all-down-the-significance-of-the-al-mahdi_b_57e93786e4b09f67131e4b52 (“For the first time in the history of the Court, an individual has been charged with the destruction of cultural heritage as a standalone war crime. Earlier international war crimes tribunals have charged individuals with the criminal destruction of cultural heritage, but only as an accompanying crime to more recognized offences such as murder and torture.”); Camila Domonoske, For First Time, Destruction Of Cultural Sites Leads To War Crime Conviction, NPR (Sept. 27, 2016) NPR, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/09/27/495606932/for-first-time-destruction-of-cultural-sites-leads-to-war-crime-conviction (“A militant has been found guilty of a war crime for intentionally destroying cultural sites — a first for the International Criminal Court in The Hague. . . . the ICC normally handles allegations of massacres and other human rights abuses.”).

[xi] ICC Convicts Al-Mahdi of War Crime for Destroying Cultural Sites, IJRC (Oct. 5, 2016), https://ijrcenter.org/2016/10/05/icc-convicts-al-mahdi-of-war-crime-for-destroying-cultural-sites/.

[xii] Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15, Judgment & Sentence, ¶ 38 (Sept. 27, 2016), https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2016_07244.PDF.

[xiii] Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15, Judgment & Sentence, ¶ 109 (Sept. 27, 2016), https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2016_07244.PDF.

[xiv] Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15, Reparations Order, ¶¶ 134-135 (Aug. 17, 2017), https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2017_05117.PDF; ICC orders former Mali Islamist to pay more than $3 million for damage to Timbuktu cultural sites, UN News (Aug. 17, 2017),

[xv] Customary Law, International Humanitarian Law, and the Laws Of Armed Conflict, Blue Shield International,

https://theblueshield.org/resources/laws/customary-international-humanitarian-armed-conflict-laws/ (last visited Jan. 15, 2022). See also Guido Carducci, The Role of UNESCO in the Elaboration and Implementation of International Art, Cultural Property, and Heritage Law, in Intersections in International Cultural Heritage Law 183, 194 (Anne-Marie Carstens & Elizabeth Varner eds., 2020) (“Treaty law and customary law are two distinct sources of international law. Each source operates under its conditions and with its legal effects. This distinction is one of principle and should not allow confusion between the two sources.”).

[xvi] Gary Solis, Attacks on Cultural Property in The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War 562, 565 (3d ed. 2021); Elizabeth Varner, Comparing Interpretations of States’ and Non-State Actors’ Obligations Toward Cultural Heritage in Armed Conflict and Occupation, in Intersections in International Cultural Heritage Law 56, 56 Anne-Marie Carstens & Elizabeth Varner eds., 2020) (“The 1954 Hague Convention . . . remains the leading treaty on the treatment of cultural heritage during armed conflict and occupation.”); Treaty Law and the 1954 Hague Convention, Blue Shield International https://theblueshield.org/resources/laws/1954-hague-convention-treaty-law/ (last visited Jan. 15, 2022) (“The key legal treaty for the protection of cultural property in armed conflict is the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. This treaty, together with its Protocols of 1954 and 1999, is the most important legal text for cultural property protection.”).

[xvii] Treaty Law and the 1954 Hague Convention, Blue Shield International https://theblueshield.org/resources/laws/1954-hague-convention-treaty-law/ (last visited Jan. 15, 2022).

[xviii] Customary Law, International Humanitarian Law, and the Laws Of Armed Conflict, Blue Shield International, https://theblueshield.org/resources/laws/customary-international-humanitarian-armed-conflict-laws/ (last visited Jan. 15, 2022). See also ICRC’s explanation of “customary international law”, Customary Law, ICRC, https://www.icrc.org/en/war-and-law/treaties-customary-law/customary-law (last visited Jan. 25, 2022) (“derives from ‘a general practice accepted as law’. Such practice can be found in official accounts of military operations but is also reflected in a variety of other official documents, including military manuals, national legislation and case law. The requirement that this practice be ‘accepted as law’ is often referred to as ‘opinio juris’. This characteristic sets practices required by law apart from practices followed as a matter of policy, for example.”).

[xix] Customary Law, International Humanitarian Law, and the Laws Of Armed Conflict, Blue Shield International, https://theblueshield.org/resources/laws/customary-international-humanitarian-armed-conflict-laws/ (last visited Jan 22, 2022).

[xx] See the International Committee of the Red Cross’s online Customary IHL database: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docindex/home (last visited Jan. 15, 2022).

[xxi] Rule 38. Attacks Against Cultural Property, International Committee of the Red Cross, https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docindex/v1_rul_rule38#refFn_49A07214_00012 (last visited Jan. 15, 2022). See also Patty Gerstenblith, The Destruction of Cultural Heritage: A Crime Against Property or a Crime Against People?, 15 J. Marshall Rev. Intell. Prop. L. 336, 352 (2016) (“Several elements of the 1954 Hague Convention had reached the status of customary international law before ratification by the United States in 2009 and as evidenced by Article 3(d) of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.”).

[xxii] Supra note xv.

[xxiii] Karima Bennoune, Cultural Heritage is a Human Rights Issue, UNESCO (Oct. 25, 2016)

https://en.unesco.org/news/karima-bennoune-cultural-heritage-human-rights-issue.

[xxiv] 1954 Hague Convention (emphasis added).

[xxv] Solis, supra note x, 567.

[xxvi] Solis, supra note x, 567; David Keane, The Failure to Protect Cultural Property in Wartime, 14 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. (Special Section: Art & War), 1, 16 (2004).

[xxvii] Solis, supra note x, 569; Zoe Howe, Can the 1954 Hague Convention Apply to Non-state Actors?: A Study of Iraq and Libya, 47 Tex. Int’l L.J. 403, 413 (2012).

[xxviii] Solis, supra note x, 570.

[xxix] Solis, supra note x, 569; Defining Cultural Heritage and Cultural Property, Blue Shield International,

https://theblueshield.org/defining-cultural-heritage-and-cultural-property/ (last visited Jan. 15, 2022).

[xxx] Prosecutor v. Al Mahdi, Case No. ICC-01/12-01/15, Judgment & Sentence, ¶ 13 (Sept. 27, 2016), https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2016_07244.PDF.

[xxxi] See e.g. Howe, supra note xxi, 413.

[xxxii] Waseem Ahmad Qureshi, The Protection of Cultural Heritage by International Law in Armed Conflict, 15 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 63, 91-92 (2017); Gerstenblith, supra note xv, 349 (“One of the main criticisms of the Hague Convention is that it does not contain provisions for punishment of those who violate its terms but, rather, relies on national domestic law to establish criminal liability.”).

[xxxiii] 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and its two (1954 and 1999) Protocols: Status of Ratification, UNESCO (Nov. 2020), http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/pdf/List-State-members-electoral-group-EN-Final-2020.pdf.

[xxxiv] Marina Lostal, International Cultural Heritage Law in Armed Conflict: Case-Studies of Syria, Libya, Mali, the Invasion of Iraq, and the Buddhas of Bamiyan, 34 (2017) (“In addition, as long as there are states bound by the 1954 Hague Convention but not by the 1999 Second Protocol (fifty- eight of them at the time of writing), the regime of special protection will continue to apply. As a result, the ordinary, special, and enhanced regimes of protection coexist, running parallel to each other.”).

[xxxv] See e.g. Howe, supra note xxi, 414; Qureshi, supra note xxv, 94; Gersetneblith, supra note xv.

[xxxvi] See e.g. Howe, supra note xxi, 420; Gerstenblith, supra note xv, 363; Patty Gerstenblith, Beyond the 1954 Hague Convention, in Cultural Awareness in the Military: Developments and Implications for Future Humanitarian Cooperation 83, 93 (Robert Albro & Bill Ivey eds. 2014).

[xxxvii] Howe, supra note xxi, 420.

[xxxviii] Culture under Fire: Armed Non-State Actors and Cultural Heritage in Wartime, Geneva Call (2018), 5,9, 15 https://genevacall.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Cultural_Heritage_Study_Final.pdf; Marina Lostal, Kristin Hausler & Pascal Bongard, Armed Non-State Actors and Cultural Heritage in Armed Conflict, 24 Int’l J. Cultural Prop. 407, 419 (2017).

[xxxix] Culture under Fire, supra note xxviii, 35; Lostal et al., supra note xxviii, 419; Kristin Hausler, Pascal Bongard & Marina Lostal, 20 Years of the Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in Armed Conflict: Have All the Gaps Been Filled?, EJIL: Talk! (May 29, 2019), https://www.ejiltalk.org/20-years-of-the-second-protocol-to-the-1954-hague-convention-for-the-protection-of-cultural-property-in-armed-conflict-have-all-the-gaps-been-filled/ (“this lack of access to UNESCO’s assistance has resulted in missed opportunities The example of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in Mali is telling in this regard.”).

[xl] Lostal et al., supra note xxviii, 419.

[xli] Blue Shield signs agreement with International Committee of the Red Cross, Blue Shield International (Feb. 30, 2020), https://theblueshield.org/blue-shield-signs-mou-with-icrc/.

[xlii] Office of the Prosecutor, Policy on Cultural Heritage, ICC (June 2021), 8-9, https://www.icc-cpi.int/itemsDocuments/20210614-otp-policy-cultural-heritage-eng.pdf.